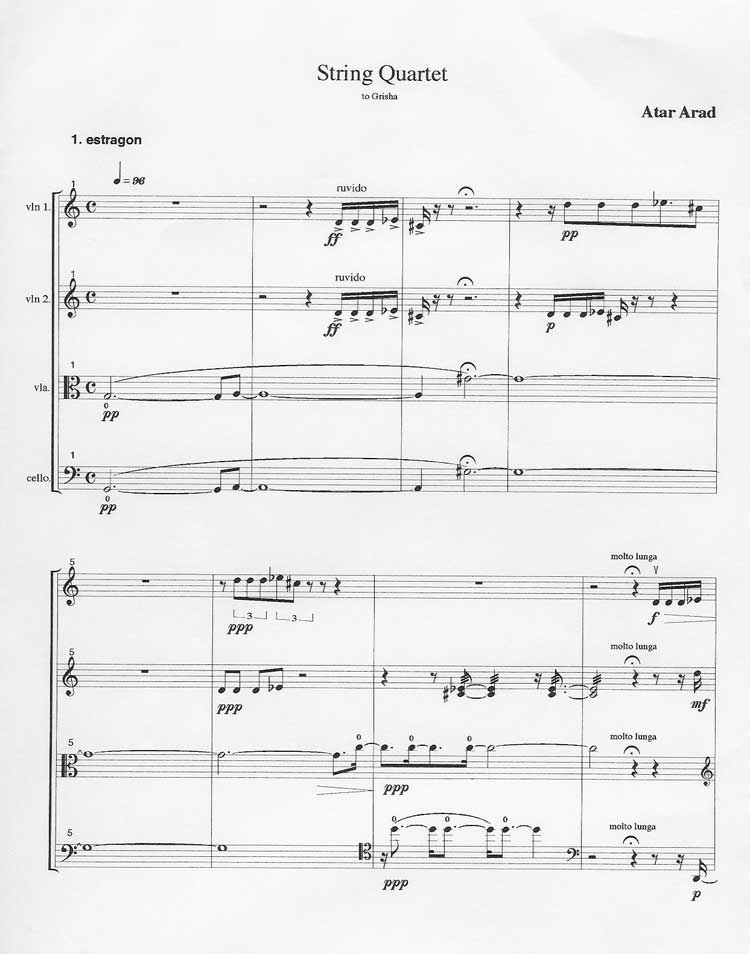

Atar

Arad

String Quartet (1998)

ESTRAGON: (giving up again). Nothing to be done.

Samuel

Beckett, WAITING FOR GODOT

-----

"IS

A KING WITH NO SUBJECT" IS A KING WITH NO SUBJECT.

Douglas

Hofstadter, GODEL, ESCHER, BACH: AN ETERNAL GOLDEN BRAID

-----

CLOV

(Fixed gaze, tonelessly): Finished, it's finished, nearly finished, it

must be nearly finished. (Pause.)

Grain upon grain, one by one, and one day, suddenly, there's a heap, a

little heap, the impossible heap. (Pause.)

I can't be punished any more.

Samuel

Beckett, ENDGAME

In 1997 I attended a couple of different performances of Samuel Beckett’s

Waiting For Godot. Taken beyond what words can describe,

I became obsessed by the play. Not unlike many other Godot

lovers, I read and reread the play, from beginning to end, from

end to beginning, in French and in English, thinking, feeling, interpreting...

I was longing for some grasp of the play’s elusive truth.

Of course, I also tried my hand at breaking the code of Lucky’s

seemingly nonsensical tirade (end of act 1), imagining that I was uncovering

a hidden message within.

As a longtime member of a string quartet, I couldn’t help seeing

Waiting For Godot as--what else?--a quartet! I wondered:

Could the spirit of the play be captured by music? Could its form? Its

atmosphere? The characters? The enigma? Given that since early adulthood

I had been quite painfully carrying within me the burden of unfulfilled

desire to compose for the genre, I felt called by this new source of inspiration,

and was about to compose the most “avant-garde” string quartet

ever written...

Something like this: The quartet is played for the most part by

two violins, Vladimir and Estragon, and a cello, Pozzo. The violist,

Lucky, attached to the cellist by means of a rope passed round his/her

neck, heavy backpack on the shoulders, is remaining ridiculously tacit

for a very long while, looking dumb and expressionless (think of Berlioz’s

Harold in Italy). Only toward the end of the first movement

does she/he burst in with an incredibly fast, rough tirade (think of Hindemith’s

Solo Sonata Op. 25 No.1 and remember that “Tonschönheit

ist Nebensache”--beauty of sound is a marginal matter). The

tirade is made of a multiplicity of distorted quotes from all over the

history of music and/or extremely condensed material from the rest of

the piece (as black holes are for the universe Lucky’s tirade is

for the play, and, sure enough, the viola’s tirade is for my music-to-be).

During the tirade, the other players disturb the violist--indeed

attack her/him by way of repetitive and unbearably violent chords. (Are

they trying to silence a messenger? In the play they try to stop the tirade

by tearing Lucky’s hat off his head....)

The quartet is in two movements (of course!); the second is the

reverse of the first (think of Berg’s Chamber Concerto).

Between the two movements, the players switch seats and turn their

backs to the audience, in accordance with the traditional

mise-en-scene of Godot. To conclude each

of the two movements a child appears on stage with a half-size violin

and plays music to match Yes Sir, No Sir, But it is the truth, Sir (think

of...well, in fact this one is a first).

The players, dressed as bums, move around the stage and do some acting

as well. They galvanize the audience with a display of an all-new

instrumental technique, crafted for the occasion by yours truly. They

fill the hall with sounds unreal; bizarre; provocative.

No doubt a tree would have to be placed on the

stage.

There. C’est fait. Done.

Or almost...

The quartet I did write requires

no trees:

With a great deal of enthusiasm and with only a vague idea of how to go

about it, I sat down to create my “quatuor fantastique.” So

as to not stare at the blank page for too long, I was toying with setting

to music “Nothing to be done,” then “Rien a faire,”

then both together. (Beckett first wrote Godot in French,

not his mother tongue. A very slight residue of “translation,”

to be found in both the French and the English versions, is in complete

harmony with the play’s unique “out of place” universe.)

Next thing I knew, I took off. I wrote furiously, obsessively, fast,

skipping meals, sleep and Seinfeld. In other words, I was

happy, but had no time to dwell on it. Before long not two, but three

related movements of music were in front of me, betraying not a trace

of my original design. Aside from Estragon’s “Rien a

faire”/ “Nothing to be done,” gone was Beckett. Gone

was the child with half-size violin and gone was Yes Sir, No Sir,

But it is the truth, Sir. Gone was the tirade and the hidden message

within, as were rope, backpack and tree. No sound-effects,

no fancy form; some dark moods maybe, but no black holes; some poignant

chords, some prolonged silence, but no offense, no provocation. The instrumental

technique on display had already been in place for a century or more before

yours truly was born. One quote, though, found its way in:

Frederick the Great, of Bach’s Musical Offering fame,

had appeared in my dream; I had been ordered to crown my second

movement, an affair of diverse fanfares and canons, with his royal theme.

I obliged.

Nothing to be done--this is the music I had to write. And

no more to be said...

Atar Arad

The quartet was premiered in April of 1999 in Bloomington, Indiana,

by a young foursome, the Corigliano Quartet. The performers were

very well dressed and didn’t do any acting on stage. Instead,

they gave a gloriously inspired reading of the piece, for which I’ll

love them forever.

Click

here to listen to an audio sample! (MP3)

To

purchase a copy of "String Quartet (1998)", contact Atar Arad

at aarad@indiana.edu |